Sound Art as ways of exploring aspects of place

Cissi Tsang

Full text | PDF

Abstract

Working within landscapes is an immersive experience, and there is an oft-mentioned sentiment of being “called” to a place or being drawn to a particular type of environment. There is also a sense of multi-layered histories when working within a landscape, with the history and features of the physical landscape intertwining with the emotional landscape of the artist. This paper seeks to interrogate how sound can be used to explore the cultural, historical and ecological aspects of place. The paper will explore the author’s own approach to soundscape composition in relation to sound artist Susan Philipsz, whose work layers fragments of the past and present through combining her voice and the immediate, everyday soundscape of place to highlight the ephemerality of memory. Philipsz’s approach will be viewed in parallel with the author’s own compositional work, with both approaches highlighting how elements of the landscape can be used as compositional elements. By being immersed in the environment and viewing the environment as an active interlocutor rather than as a passive resource, these methods invite listeners to alternative ways of listening and understanding place.

Keywords

Soundscape, composition, field recording, experimental, place

Introduction

When I first developed an interest in landscape-based art, I was particularly struck by the richness of narrative that accompanies a place. From that starting point, I wanted to find methods of sharing my reflections to audiences. Much of my work since then has been based on visiting places and deriving works from visits.

As I worked more extensively within landscapes, I became acutely aware of the cultural, historical and ecological aspects of place. I also became aware of my own responses to these aspects, and how they interacted with my personal history. From these experiences, I became drawn to methods of incorporating landscape into works as a way of conveying narrative, emphasising aspects such as using the physical shapes and aspects of the landscape as part of the composition, and conveying the dialogues occurring between myself and a place.

In this paper, I will initially offer a brief overview of landscape as narrative, with a focus on Scottish sound artist Susan Philipsz, followed by a discussion of two of my works inspired by Philipsz’s conceptual approaches – Automata (2020) and The Drowning (2018).

Landscapes as Narrative

Landscapes are fertile places for creating and inspiring works, with past and present constantly intersecting as an individual traverses across geographies and immerses themselves. This process of immersion into place encourages the creation of multiple forms of dialogue – firstly, within the artist themselves as they process thoughts and emotions a landscape triggers within them, then secondly between the artist and the landscape as they consider navigational methods over the land’s geography.

How sound interacts with place can become quite apparent while traversing a place. There are different reverberations depending on the geography of place – such the shape and positioning of rocks, the sounds of moving water and wind and the location of buildings. Depending on the location of the traveller, certain intersections of sounds can become very clear – from the changing sound of footsteps across varying terrain, to the sound of the natural inhabitants of a place (birds, trees, animals) interacting with each other.

Any discussion of place requires unpacking of the meaning of ‘place’, and how such a definition can be applicable universally. In the simplest sense, place is used to refer to either a location or the occupation of said location, differentiated from the concept of ‘space’ due to its increased specificity. Beyond that though, creating more nuanced and detailed definitions can be difficult at best, with multiple attempts at conceptualising what place means. The idea of ‘place’ covers cultural, social and personal expectations, as well as geographic boundaries and shapes. Some attempts to acknowledge and incorporate these myriad aspects include John Agnew’s definition of place as a threefold process – physical place (as a location), relationship of a site to its spatial boundaries (the locale), and the cognitive and physical interactions between human and site (sense of place) (Agnew, 2011).

The physicality of landscape itself shapes much of the human experience of the land – for instance, in the ways in which we use physical demarcations and descriptions for place, and how we determine our movements within these boundaries. Much has been written about landscape and the human experience, particularly in regards to psychological and spiritual connections and landscape as a cultural construct. Art historian, William John Thomas Mitchell, writes that landscape should be thought of as “a process by which social and subjective identities are formed” (Mitchell, 1995, p.1). In his theses on landscape, Mitchell notes that “landscape is a medium of exchange between the human and the natural, the self and the other” with a “potentially limitless reserve of value” (Mitchell, 1995, p.5). Further in his thesis, Mitchell writes that “landscape is a natural scene mediated by culture. It is both a represented and presented space, both a signifier and a signified, both a frame and what a frame contains…” (ibid).

In essence, when it comes to landscape-based art, the landscape itself is a co-creator of the work, through its presence as a powerful, elemental, dynamic entity. This relationship is also seen as on-going and evolving where the landscape is more than an external object, but one where people and land are engaged in constant co-constructing of relationships (Wylie, 2007). This approach to the landscape views the relationship between people and land as active, embodied and dynamic, with the landscape comprising the totality of relations between people and land.

Sound is a powerful way for artists to reflect upon their reflections of a place – the history, the geography, and their own emotive responses. Sound can be the conduit for mediating knowledge and imagination – where concepts of landscape, place and meaning can be situated together. For instance, the contours and resonances of the land can be captured and expressed through field recordings, i.e., the rushing cascade of water onto rocks, the wind through trees, and the animal sounds highlighting its inhabitants. The history of a place can be alluded to through using fragments of historical texts, or by manipulating field recordings to evoke the past. These aspects can then be used by the artist in the creation of artefacts that channel these emotions and memories.

The act of listening in itself is a powerful factor in working with place and sound, and particularly with finding connection between person and place. Composer and theorist Pauline Oliveros advocated the concept of ‘deep listening’ to foster greater connection between person and place, through sound. The concept of listening did not always equate to merely hearing a sound, as Oliveros explains:

Listening is not the same as hearing and hearing is not the same as listening. The ear is constantly gathering and transmitting information – however attention to the auditory cortex can be tuned out. Very little of the information transmitted to the brain by the sense organs is perceived at a conscious level (2005, p.1).

Listening, therefore, implies a sense of intentionality on part of the person – the person must want to seek these sounds, and to choose to pay attention to these sounds. Listening therefore encompasses both the physical aspect of hearing (i.e., turning frequencies into information) and the psychological (i.e., the effect of sound on an individual). There is a sense of embodiment with listening, and also an active reflection on part of the artist in how these aspects of listening impact on interactions with place.

A common sentiment amongst sound artists working within landscapes is the sense of being “called” to create work in an area. There is no separation of artist and place – the artist is an active agent while in the place, bringing with them past memories and experiences as they engage with the land. This intertwining of the histories between artist and place is an important facet of the creative process.

One artist who draws on these concepts for their compositional practice is Drew Mulholland, whose works draw on his experiences and reactions to memories and places through a combination of field recordings and manipulations of sound. Mulholland noted that in his work, “…you can’t help but bring your own reaction to it [the place], and maybe that’s where part of the strength of it is: the fact that the place is kind of channelling something for you. Do you know what I mean? It’s a kind of conduit if you like” (Mulholland, Lorimer and Philo, 2009, p.391). In Mulholland et al’s work, the emotionality of a place is expressed not only by the inspiration of being present in a place, but also through deriving compositional elements from the place by using elements from the landscape itself through field recordings. With such a practice, the landscape becomes an integral part of the compositional process itself.

The concept of landscape channelling emotions is one that Mulholland often states about his work. There is no separation of artist and place – the artist becomes an active agent while present in the place, bringing with them past memories and experiences as they engage with the land. This intertwining of the histories between artist and place is an important facet of the creative process. During another part of the interview, Mulholland noted the power of landscape on memory, particularly on the impact on interpretations of place. In this section, the question of psychological emptying was raised, and subsequently rejected by Mulholland:

Chris Philo (CP): You’ve never attempted a phenomenological emptying of yourself before the place, so you become like completely a blank screen and you’re trying to hear the place for itself?

Drew Mulholland (DM): No.

CP: No? It’s always [the] relation between yourself and the place.

DM: Yeah, I think so. Yeah, I think for me it’s got to be, because there’s even things that you might think you’ve emptied, but you bring to it and later you realise, ‘Oh, that’s, that’s where that’s from’ (2009, p.391).

Exploring place through sound is also reflected in Michael Gallagher’s works, which he describes as a form of ‘audio drifting’ (Gallagher, 2014). Also interwoven into Gallagher’s work are plays on temporalities, where multiple temporalities can exist together within the same period. In Kilmahew Audio Drift No 1 (2014), a large part of his work involved recording his own movements across a landscape over time, then overlaying these recordings and allowing listeners to wander the landscape without a set route while listening to these recordings over headphones. Listeners could then choose the volume of the recordings in relation to the current soundscape. This resultant juxtaposition of the soundtrack and the natural soundscape therefore offers a sensation of ‘multiple temporalities’, where there are potentials for “…constructing alternative versions of the past, and for recouping untold and marginalised stories” (Gallagher, 2014, p.471).

Another artist who shares these sentiments about exploring concepts of place and history through sound is Susan Philipsz, who creates public sound installations that often reflect on the history of a place, as well as her emotional responses. Reflecting on how she initially begins work on a sound installation, Philipsz notes that, “Usually the space comes first. I go, have a look, and find something that draws me in. I search for something, a hook, which can be the architecture, the acoustics, or the history. More and more it’s about the history of a place” (Buhmann, 2017, p.44).

Susan Philipsz

Susan Philipsz is a Scottish artist who began her career in sculpture, before moving into sound installation. While studying sculpture, she developed an interest in the relationship between sound and architecture, particularly in the act of physically projecting her voice into a space, as Philipsz explains: “You become aware of how sound relates to the architecture and that can draw your attention to its physical characteristics, how sound can define distance or how sound can cut through space” (Philipsz, 2016, para. 4). Much of her work centres on the themes of loss, hope and return, and her practice contemplates the evocative nature of sound in triggering memories and emotions for listeners. Philipsz is intrigued by how sound can act as a conduit for dialogue between listener and place, and in particular how the “emotive and psychological effects of sound can heighten your awareness of the space you are in” (Corner, 2010, n.p.).

Many of Philipsz’s works are installed in public places, with Philipsz engaging with a place’s historical, social and cultural contexts during the creative process. Philipsz’s work often consists of recordings of her voice, played in various locations through speakers around an area. The recordings are unadorned – she sings unaccompanied and her voice is untrained, and these aspects lends additional layers of intimacy and fragility to the works. Philipsz notes about her own voice:

“…The resulting gaps, silences and absences where the instrumentation should be, are suddenly more apparent and you become more aware of the intimate and personal, aspects of the voice. The pauses and the breathing are all more apparent. The way I sing is also quite natural and untrained so there is the sense it could be anybody’s voice. I think that helps to connect directly with the viewer. Everyone can identify with the human voice. The timber, intonation of the unaccompanied voice, the spacing of the words and the tune can be emotive in itself. Also the disembodied voice, floating in the air, not attached to a body, makes it more spectral. Sometimes it appears to emerge from the space itself…” (2016, para. 6).

Philipsz’s works offer a multi-layered experience of place for the audience – starting with the initial engagement of her voice, then an awareness of her voice intermingling with the everyday sounds of the immediate environment: “What I try to achieve in my installations is to become aware of the space you’re in and to become aware of yourself in that space. It’s a simultaneous experience of being with the sound but also grounded in the present” (Philipsz, 2016, para. 5). Philipsz is particularly interested in fostering a sense of collective intimacy and awareness within audiences, particularly when they are waiting in expectation for her work to begin, and has observed changes in audience perspectives during performances of her work – from an introverted focus on their own experiences, then an acknowledgement of a collective experience: “It’s very intimate and creates a feeling of solitude and time passing, but then everyone is having this collective experience, and you become extremely aware of your environment…” (McAnally, 2020, para. 5).

An interesting aspect of Philipsz’s work is her use of sound to draw attention to the relationships between listener and environment, and also listener and the history of place. Often, her works are based upon an aspect of history from the place itself, creating an experience where often, the past meets the present. Philipsz elaborates on this in an interview about her approach to sound:

“The possibility for a layered experience is certainly there. Sound is visceral, and you respond to it immediately according to how it works spatially and sculpturally, to how it resonates with your body…Then, when you become inquisitive about what this particular sound is or what that specific conversation was based on, you can go deeper into it” (Buhmann, 2017, p.45).

One example is her Turner Prize-winning work, Lowlands (2010), an installation work featuring recordings of Philipsz singing “Lowlands Away”, a Scottish lament about a man drowned at sea who returns as a spectral being to farewell his lover. The work was originally installed under three bridges – the George V Bridge, the Caledonian railway bridge, and the Glasgow Bridge – over the Clyde River in Glasgow, with her voice singing different parts of the song.

Lowlands highlights the complexities in Philipsz’s works and conceptual approach. There are interplays between artist and landscape, and listener and the environment. Her sombre, looping vocals – via the speakers – interacts with the immediate environment through echoing and reverberating on (and through) the physical entities of the place. By the time each recording has reached the ears of listeners, it has been shaped and sustained by the stone and metal architecture of the bridges and the waters flowing underneath. Her voice, much like the protagonist in the lament, is an echo – one that recalls the history of the area, marking the passage of time and the loss of what once was.

Not only does her voice interact with the physical elements of the environment, but it also interacts with the immediate soundscape. Her voice invites listeners to pause from their usual listening habits – the largely unconscious ways in which people navigate areas sonically through backgrounding the immediate sound environment – and to encourage a deeper listening experience. Philipsz “…creates a keen awareness of landscape as active resonating and sensitive interlocutor rather than as passive resource” (Comstock and Hocks, 2016, p.166). Alongside her voice, Philipsz draws attention to the myriad facets that make up the soundscape – as she broadcasts over the river, her voice harmonises with such elements as the sounds of water birds, the movement of water against the shore, and the passing of trains overhead. The sound of her voice also changes depending on where the listener is situated – if they are walking, swimming, boating or driving along the bridges.

Another example of Philipsz’s approach to temporality and place is the piece Day Is Done, a permanent sound installation at Governor’s Island, New York. Drawing on Governor’s Island’s military history, two speaker systems located at different parts of the island will each play two of the four notes that make up Taps – a bugle call played by the United States Armed Forces – at 6pm. Depending on where the listener is at the time, they will either hear sections (when on the island) or the full piece (as they are on the ferry, departing the island).

Philipsz’s works draw the listener towards the present – by becoming aware, then focusing on her voice, the listener’s attention is inevitably drawn towards the other sounds that make the soundscape of the area. Philipsz notes, “It’s funny when people recount their experiences, they often describe the physical conditions at the exact time they heard the work, like they are hyper aware of everything around them at that moment in time” (Philipsz, 2016, para. 5).

Philipsz’s focus on loss and mourning also extends outwards, into commentary about loss in the environment. Her installation work White Flood (2019), as part of the Seven Tears series, plays on ideas of separation and absence. The work, which culminates in amidst twelve-channels of split sound, is a reflection on climate change and the surrounding anxiety around collapsing environments. The audio for White Flood is a modified version of composer Hans Eisler’s score that accompanied the original film, with each instrument represented by a single tone being played through a separate speaker. The result is a work filled with moments of dramatic runs and staccato rhythms contrasting with silence, with this juxtaposition suggesting that such environments could be lost to us in time.

Automata

Like Philipsz, I started my artistic practice in another discipline (photography), then gradually moved into sound as I became increasingly drawn to its visceral nature. As my practice developed, I became interested in incorporating physical elements of a landscape into soundwork as another way in which to have a dialogue with the landscape. I strongly resonated with Philpsz’s concepts around the interaction between sound and physical elements, and I was particularly interested in using physical elements of a landscape as a way of generating sound for a composition, and viewing these physical elements as additional instruments.

One of my works that explores the interplay between artist, soundscape and physical elements of the landscape is Automata (2020), an audio-visual piece that was commissioned by Tura New Music’s @theRoots program. The piece contemplates the interplay between machine and nature, and is also part of a greater exploration within my practice of combining automated graphical sequencers with aspects of nature. I also wanted to create a piece that highlighted the delicate balances in the ecosystem.

The piece is based upon a photograph of water droplets on Warren River near Pemberton/South West Boojarah Region, Western Australia, accompanied with field recordings from the same area. In 2017, I spent some time walking along the banks of the Warren River, admiring how beautifully melodic the ripples appeared as they intersected and danced around each other. I also admired how full of life the river was, both above and below the surface, and the importance of this river to the South West’s ecosystem. I also wanted to portray the fragility of the place, and how the calm exterior of the river belies a sense of urgency for survival underneath the surface.

As part of my documentation, I took some photographs of the area, as well as some field recordings. The field recordings were initially recorded on a Zoom H1 handheld recorder. The field recordings were edited in Adobe Audition, for length and clarity (using Audition’s multiband compression), and then were placed into Ableton to act as a point of context (and place marker) for listeners. The intention of these field recordings was to imply the listener themselves was at the banks of the river, listening to the sounds of the area while gazing downwards. From the series of field recordings done by the side of the river, two of them were used to represent the area – one of frogs and insects, to highlight the ecology of the river, and the other of moving water, to denote the movement of the Warren.

Figure 1. Photograph of ripples on the surface of the Warren River. (author supplied)

Figure 1. Photograph of ripples on the surface of the Warren River. (author supplied)

One of the goals for Automata was to have a visual element that was both a narrative device and driver of sound. From a compositional perspective, I wanted to explore the use of visual elements of a place to drive sound in a composition, and particularly wanted to emphasise the importance of place in the composition itself. I used one of the photographs of the ripples in the water as the base image for the work (figure 1). The water droplets struck me as an apt reflection of fragility – as the circles made by these droplets are quickly broken and scattered.

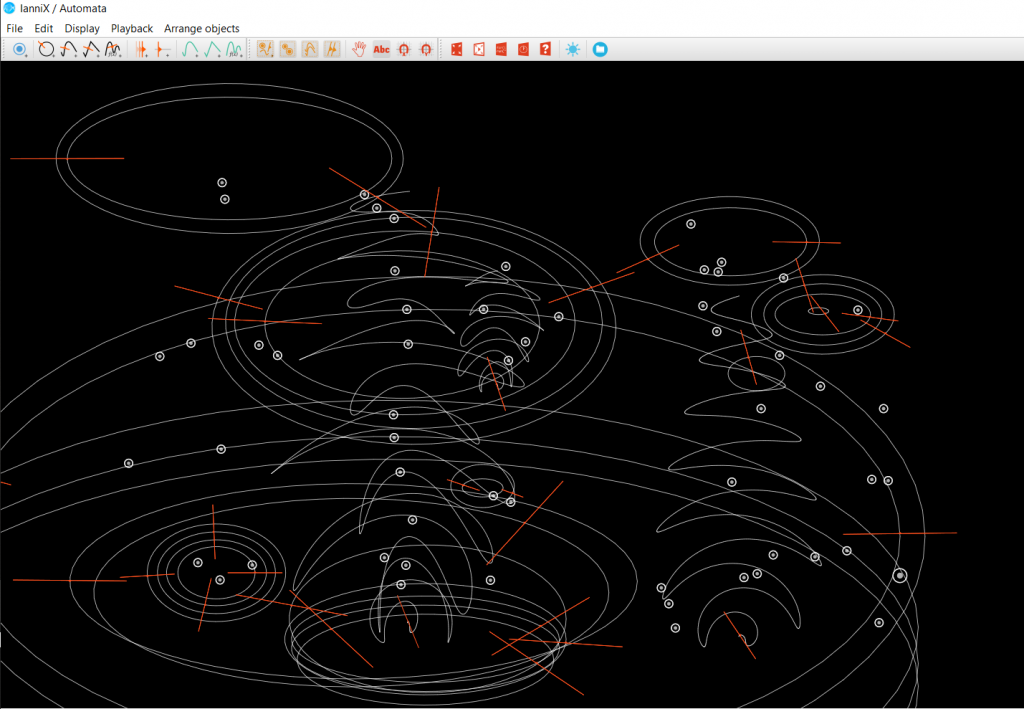

To render the image into an autonomous musical instrument, I used a program called Iannix (an open-sourced, real-time graphical sequencer, based on composer Iannis Xenakis’s visual approach to composition) to trace the shapes of the ripples. Iannix can be used to create an autonomous instrument where lines and curves can be played using cursors and triggers, with the horizontal positioning of these triggers corresponding to pitch, so these lines and curves became the basis for triggers and cursors that would operate the instrument (figure 2). As each cursor (in red) moved across a trigger (white dots), a note would sound. I positioned the triggers based on the darker spots on the photograph. Some of the spots are from droplets, others from refractions of the light, vegetation and forest debri.

Figure 2. Shapes and curves created in Iannix as part of the piece, based on the photograph of the ripples. (author supplied)

To heighten the sense of frantic energy and urgency in the movement of the cursors, I removed the visibility of the cursor paths by changing the visual settings. By using Iannix’s “light” mode and turning the cursor paths white, the viewer is left with the sight of the cursors moving alongside – and sometimes against – each other while trigger points flash on and off the screen. I also found the effect of removing the cursor paths made the movement of the cursors seem almost organic, because their movements are not immediately telegraphed to the viewer.

To link the Iannix instrument to Ableton, I used LoopBe1, a free virtual MIDI driver that sends all MIDI output data to a receiving application in real time (as Iannix’s output is MIDI). Through this, I was able to have the Iannix instrument playing alongside the field recordings, which I placed in Ableton 10 as separate tracks. For the sound of the instrument, I chose a bell-like sound as I realised that due to the number of cursors and trigger points, I required sharp and clear tones so that the various overlaid harmonies and counterpoints as the cursors moved could be clearly differentiated.

Figure 3. A screenshot from the completed version of Automata. (author supplied)

The full piece (06:00) can be viewed here: https://www.tura.com.au/tura-program/tura-adapts-2020-commissioning/theroots-c-tsang/

The Drowning

The Drowning was inspired by Philipsz’s concept of overlaying history with the modern day, and the use of history and landscape as a form of inward reflection. I was particularly interested in interrogating how sound can be used as a way in which the history of a place can interact with memories of past trauma. Much of the conceptual basis for this work was informed (and inspired) by Philpsz’s work War Damaged Musical Instruments (2015).

War Damaged Musical Instruments features fourteen recordings of British and German brass and wind instruments that had been damaged in conflicts, playing notes based on The Last Post. Some of the instruments have been so extensively damaged (as with a shofar that was found, completely flattened, beneath a pile of coal a Jewish family had buried for safety before fleeing their home), with Philipsz noting that, “I am less interested in creating music than to see what sounds these instruments are still capable of, even if that sound is just the breath of the player as he or she exhales through the battered instrument. All the recordings have a strong human presence” (Philipsz, 2015, para. 3).

Drowning was created as part of a week-long artist residency at Bundanon Estate, New South Wales Australia, through the Bundanon Trust in 2018. My intention was to immerse myself with the area and gather source materials to create works. As part of my research into the history of the area, I came across a drowning incident that occurred in 1922.

The Bundanon Estate is situated on the banks of the Shoalhaven River – a tidal driver with a reputation for being deceptively deep and turbulent (figure 4). The dark waters of the river disguise the rapid undercurrents and sudden drops on the riverbed, and in 1922 two riders drowned in the river after their horses struck trouble in unexpectedly deep water (Bundanon Trust Archive, n.d.).

Figure 4. An aerial photograph of the Shoalhaven River. (author supplied)

This tragedy reminded me of an incident when I almost drowned as a child and stuck in my mind as I walked along the banks of the Shoalhaven. I thought about how to best respond to this aspect of shared history. As I walked along the Shoalhaven, I took several field recordings, with two recordings in particular becoming the basis for this piece – one at the shore with the sound of a plane overlapping the waves, and a hydrophone recording.

When creating this piece, I thought back to my experience of near-drowning. I recalled three distinct parts, which I recreated in the piece:

- The initial drowning, as I fell under the surface of the water;

- The experience of an altered reality while underwater;

- The eventual rescue and the sensation of re-surfacing.

With the first section, I wanted to emphasise the loudness of the environment which seemed to be amplified by my struggling, followed by the sensation of the world being muffled as I went under. I wanted to represent that feeling of going under by gradually slowing down the field recording from its original length to 8x, through an audio time and pitch stretching process in Adobe Audition. This process allowed me to simulate the idea of time seemingly altering, and to enhance that feeling of altered reality, I also cross-faded the surface recording of the river with the underwater recording via hydrophone.

When I was under water, it felt like time had slowed (I was told later it was not a long time) and I felt an eerie sense of calmness and peace as the world began to darken. To represent this sonically, I used a slowed version of the field recording (also to 8x, but this time slowed from the start of the recording), layered with multiple versions of the slowed field recording running through various resonators in Ableton. These resonators are a type of pitched reverb, which oscillate to certain pitches and frequencies depending on their settings. Resonators are useful for creating eerie, rhythmic tones, and in this context, they were particularly useful in creating a ghostly effect in the piece.

Lastly, I remembered the world rushing back as I was lifted out of the water and how it felt as I resurfaced. For the final section of the piece, I repeated the first recording of the river over the surface, and to represent the feeling of life rushing towards me, I included parts of another field recording taken from another part of the estate, of birds calling to welcome the morning.

The full piece (05:40) can be heard here: https://samarobryn.bandcamp.com/track/the-drowning-disquiet-0337

Conclusion

Sound encourages listeners to form alternative perspectives to a place. Places are often ignored and their presence taken for granted. Sound invites listeners to stop, float across temporalities and to re-imagine their relationship with place, rather than viewing a place as spaces between points, or as pathways to destinations. Through methods such as sound installations, using field recordings and basing parts of works on the contours of the landscape, the boundaries between landscape and culture, and the interior and exterior, all become permeable.

Sound also allows artists to engage with the audience, either through being a spectral presence in public spaces, or as a conduit for listeners to explore an artist’s personal history. Philipsz has often noted the ability of sound to foster a sense of intimacy amongst audiences through a shared experience. I have had similar experiences – although my work exists within the digital realm, the concept of shared listening remains. The ephemerality of sound reflects the ephemerality of being, and the fragility inherent in our relationship with place. Sound is a way of disrupting our daily routines of (not) listening, and encourages us to become more grounded and aware of our surroundings.

References

Agnew, J.A. (2011). “Space and Place” in J. Agnew and D. Livingstone eds., Handbook of Geographical Knowledge. London: Sage.

Buhmann, S. (2017). In Search Of Resonance – A Conversation With Susan Philipsz. Sculpture, 36:9, 43-47.

Bundanon Trust Archive. (n.d.) A great shock: The Drowning Fatality. Retrieved from https://www.bundanon.com.au/place/social-history/bundanon/mackenzies/drowning-fatality/

Comstock, M. and Hocks, M. (2016). The Sounds of Climate Change: Sonic Rhetoric in the Anthropocene, the Age of Human Impact. Rhetoric Review, 35:2, 2165-175.

Corner, L. (2010, November 14). The art of noise: ‘sculptor in sound’ Susan Philipsz”, The Observer. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2010/nov/14/susan-philipsz-turner-prize-2010-sculptor-in-sound.

Gallagher, A. (2014). Sounding ruins: reflections on the production of an ‘audio drift’. Cultural Geographies, 22:3, 467-485.

Oliveros, P. (2005). Deep Listening: A Composer’s Sound Practice. New York, USA: iUniverse, Inc.

McAnally, J. (2020). Sound and sculpture: Susan Philipsz interviewed by James McAnally. Bomb Magazine. Retrieved from https://bombmagazine.org/articles/sound-and-sculpture-susan-philipsz-interviewed/.

Mitchell, W.J.T. (1995). Landscape and Power. Chicago, USA: University of Chicago Press.

Mulholland, Drew., Lorimer, Hayden. & Philo, Chris. , ‘Resounding: An Interview with Drew Mulholland’, Scottish Geographical Journal, 125:3-4, 2009, 379-400.

Philipsz, S. (2015). War Damaged Musical Instruments [Recordings]. Tate Britain Exhibition, London, UK. Retrieved from https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/susan-philipsz-war-damaged-musical-instruments..

Philipsz, S. (2016). Reverberations: in conversation with Susan Philipsz. FOURBYTHREEMAGAZINE. Retrieved from http://www.fourbythreemagazine.com/issue/silence/susan-philipsz-interview.

Wylie, J. (2007) Landscape. Abingdon, England: Routledge Press.

About the Author

Cissi Tsang is a nonbinary audio-visual artist living in Perth, Australia. Their work explores the emotional nature of landscape, and their response to the natural landscape as a composer and performer. Part of their practice involves incorporating audio and visual elements of place into compositions, and using the landscape as a narrative device. Cissi is currently a PhD candidate at the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts (Edith Cowan University).

To cite this article

Tsang, Cissi. “Sound Art as ways of exploring aspects of place.” Fusion Journal, no. 19, 2021, pp. ???. http://www.fusion-journal.com/Sound Art as ways of exploring aspects of place/

First published online: February 2021